#NEPTUNES MISSIONS DRIVERS#

One of the major drivers behind the decision whether or not to exercise this option was Saturn’s largest moon, Titan (see “The mysteries of Titan”, The Space Review, November 8, 2010). In 1974, it was discovered that in addition to the Jupiter-Saturn launch window in the late summer of 1977, there also existed an overlapping launch window that allowed a spacecraft to follow a slightly slower trajectory that could continue on to Uranus and Neptune after passing Saturn. While NASA attempted to salvage more of their Grand Tour using Voyager-class spacecraft including a “Mariner Jupiter-Uranus 1979” proposal, in the end they never advanced beyond paper studies because of the lack of available funding, as well as a much less expensive (but riskier) option.

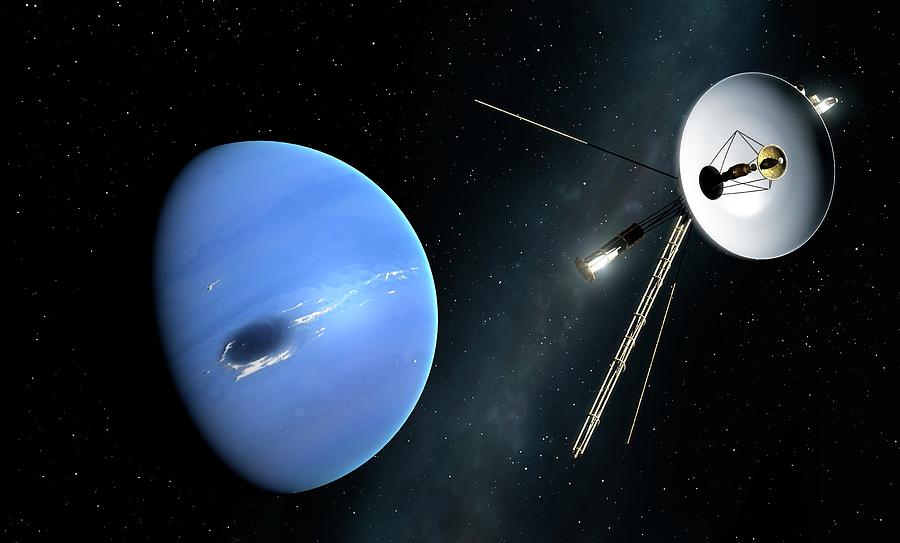

Originally designated “Mariner Jupiter-Saturn 1977” but renamed “Voyager” in early 1977, this more modest mission was managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and could be completed with a shorter flight time of four years at an estimated cost of $250 million. Unfortunately, NASA’s plans for the Grand Tour proved to be overly ambitious and far too expensive with an estimated price tag of $900 million (equivalent to over $5 billion today.) In 1972, NASA scaled back the mission to a single pair of Mariner-class spacecraft that would take advantage of the 1977 launch window to Jupiter and Saturn. This Grand Tour would be completed when the last of the second pair of spacecraft reached Neptune in early 1988. Another pair would be launched in 1979, first towards Jupiter and then on to Uranus and Neptune. While many options were considered, among the more widely disseminated involved the launch of a pair of spacecraft in 1977 that would explore Saturn and Pluto after their JGA. This flight time was many times longer than had been demonstrated by any spacecraft at that time and would require many engineering advances. NASA planners originally envisioned building a set of highly advanced, nuclear-powered probes called TOPS (Thermoelectric Outer Planet Spacecraft) capable of studying a succession of outer planets during a decade-long mission. The option for Voyager to continue on to Uranus was publicly downplayed by JPL in the months leading up to launch, while the Neptune option was never even mentioned. In 1969, NASA formally began design of the mission that was popularly referred to as “The Grand Tour.” By using this Jupiter gravity assist (JGA) technique, a larger payload could be launched and reach its destinations faster than was practical using a direct flight. In 1965, Gary Flandro discovered that as a result of a rare alignment of the outer planets that occurs only once every 176 years, it would be possible to launch a probe to Jupiter in the late 1970s and then have it fly by successively more distant planets for a reconnaissance of all the outer planets. The origins of the Voyager mission to Neptune can be traced back almost half a century to work originally performed by a NASA summer intern. The launch of Voyager 2 on a Titan IIIE-Centaur on August 20, 1977.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)